After a few days touring Beijing and seeing the normal Great, Forbidden and Heavenly sights, I noticed the guidebook mentioned the Peking Man Site in Zhoukoudian as being reasonably nearby. After several days of temples and castles and with the Chinese National Holiday promising to swamp every tourist location in Beijing, I thought it might be nice to take a trip out to see Peking Man’s cave.

I can’t really do a good look at the literature since most of the stuff is in Chinese or too old to access easily while traveling (made even more difficult thanks to China’s Great Firewall). But from what I gathered from some Googling and the site’s museum, Peking Man was actually the fossilized remains of a bunch of male, female and child (they weren’t too big on political correctness back then) Homo erectus, the hominid (almost but not quite human [i.e. cavemen]) species thought to be closest related to humans. Bones were first found in Zhoukoudian in 1923 and pieces from several individuals were found before World War II. At the start of the war, the scientists decided to send the bones to America for safety but somewhere along the way the shipment disappeared. This was a major loss to science (but luckily there were some casts made of the fossils so at least some information is still available). Effort to track down the missing fossils was renewed in the last couple years but their location remains a mystery. Since the loss, further excavations have turned up additional specimens including additional parts of of a prewar skull. The bones are estimated to be between 500,000 and 250,000 years old.

Interestingly, although Homo erectus lived in Asia for hundreds of thousands of years, genetic analysis of 12,000 men across Asia showed that all had a mutation in the Y chromosome though to have originated in Africa in the last 90,000 years. This likely means that modern humans (H. sapiens) migrated out of Africa and displaced/eradicated the native Peking Men (H. erectus).

Anyway back to the travel. Unfortunately, it turned out that the holiday also swamped the bus and the highway so I was stuck standing squished in the aisle while the bus crawled through a three hour traffic jam. Once we finally got to Zhoukoudian, the buildings and houses on the walk to the site looked a little run down but everyone we asked for directions met was very friendly with a few kids even playing the yell “Hello!” at the foreigner game.

The guidebook describes the site as “geared towards specialists” and “suffer[ing] neglect recently” so I was a bit worried. But I was pleasantly surprised when I arrived. It seems quite well maintained and, in fact, it seemed they had an overabundance of staff (although no English speakers) probably due to funding from it’s World Heritage designation. Most of the museum has English captions and I found it pretty interesting. The high point was of course the hominid bones from the site. Most of the bones were labeled as reproductions but a few were not. I don’t know if that means those bones were real or just that someone forgot the label. Hopefully it was the former. The museum also had some of the stone tools made by the ancient people and evidence of fires. The museum claims that there are several layers of the excavation that were full of ash but I’ve since read that this evidence of fire use is disputed. Recent more detailed examination found that this ash-like material was actually not ash but deposits from a quiet pond type environment although there were definitely a lot of burned animal bones. This makes the claim that Peking Man used fire questionable although it seems to me (note I’m not a anthropologist) like a body of water in the back of a cave might make for a good garbage disposal (which on further investigation seems to be roughly what this scientist is saying).

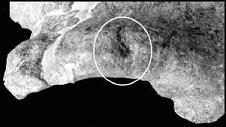

The museum also shows some rather formidable skulls of giant hyenas found in the cave. These hyenas seem to have alternated habitation of the cave with Peking Man and several layers of the excavation had numerous hyena poop fossils (called coprolites if Jeopardy ever asks). Some scientists suggest that Peking Man did not actually live in the cave and that the bones found are just the unlucky prey of the hyenas. The most recent article (currently directly available here) I could find (in my limited search) weighs in strongly for this hypothesis. The researchers point out that only fragmented pieces of bones have been found and that most arm, rib and leg bones are missing just like in modern hyena dens. They also looked at all the bones and suggest that almost all of them show marks of large predator chewing (one example shown in the picture to the right). But they do point out that there are numerous artifacts and burned bones found from within the cave so Peking Man must have had at least a “transient” (I’m not sure what transient means when the time scale is measured in hundreds of thousands of years) presence. I was a bit disappointed at first when I read this but then I realized I had been to the site of a 200,000 year battle between (almost) humans and beast.

I managed to get side tracked by the science again. Back to the travelling. After the museum, there is a nice little path that visits the remnants of the famous cave. I believe most of the cave collapsed some thousands of years ago and there have been intense excavations so I’m not exactly sure what part of this is actually where the hyenas and Peking Man would have been but it’s still pretty cool to walk inside and see it. Megaphone toting tour guides come through every 10 minutes or so but if you get there in between them you can actually have the whole place to yourself. Which reminds me, even during Golden Week the site was not busy. I guess it’s too far (although not that far if you’re not stuck in holiday traffic) out of Beijing and not as catchy as the (hundreds of times younger) Great Wall or Ming Tombs.

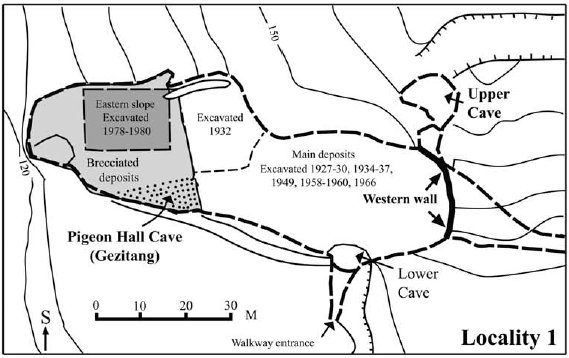

After the cave, we came to what was for me the most striking part of the tour, the location where the main excavation had occurred. Scientists had dug more down more than 100 feet into the dirt and debris filling the old cave and found bones throughout. This really brought home that fact that Peking Man had been living in (or around) this cave long enough for 100 feet of dust and debris to build up. 250,000 years. More than 3,000 (modern) lifetimes. 60 times longer than recorded history.

I wasn’t sure if this was the actual excavation site but this article about fire use shows this very location (shown to the right) being researched. Definitely a very cool site and well worth visiting even with the traffic and sardine-like bus experience (which should be an unusual event).

Directions

To get there, take bus 917 from Tianqiao Station in Beijing (9 å…ƒ [$1.5]). But you have to be careful because there’s 4 or 5 different 917’s, you want the plain 917 without the extra symbols. Once you get on the right 917 go until Zhoukoudian (周å£åº—) Daokou station (actually just a sign next to the road). The bus station should be on one leg of a T-intersection. To get to the Peking Man Site, walk back to the T, turn left (away from the gas station) and walk about 15 minutes. Once you cross a bridge over a small creek the road should turn right and the entrance to the Peking Man continues straight. Or you could just take a taxi which shouldn’t be more than 15 å…ƒ ($2). The ticket for Peking Man Site was 30 å…ƒ ($4).

This article provides a decent (although biased towards Peking Man) review of the science and theories surrounding the site. It might be worth a quick skim if you’re planning on going and don’t feel like reading any of the ones above (I wish I would have read up a bit first to appreciate the site better but it was a spontaneous visit). This recent article mentioned above provides a more hyena-oriented perspective and some nice maps (which I wish would have been shown at the site so I’ll include one of their several below).

Alex | 06-Mar-08 at 4:45 pm | Permalink

Cool, dude. I appreciated the details about these Peking fellows.

Makes me hope 10,000 BC turns out to be good.

ScottS-M | 06-Mar-08 at 5:13 pm | Permalink

That sounds like an interesting movie (except I thought people were still figuring out you could plant stuff and eat the results and the trailer shows pyramids and sail boats). Oh and it comes out tomorrow. I might have to do another trip to the $5 morning theater.